(Click on the links embedded in location names to see them on Google Maps.)

Right at the border of Yellowstone National Park is this monument to the railroad's influence in the development of the park.

The branch was built by the Oregon Short Line from 1905 to 1907 to tap into the growing tourist traffic that exploded in the late 1890s. Yellowstone National Park had railroad access via the north entrance from the Northern Pacific so the OSL sought to break open the NP monopoly and allow access for tourists from the southern half of the country. The west entrance and the town of West Yellowstone themselves are the direct product of the railroad and would probably have never existed without it - before the railroad began construction from Ashton, West Yellowstone was simply unsurveyed Forest Service land. Unfortunately Passenger traffic on the Yellowstone Branch ended in 1960 and the rails were torn up from West Yellowstone to Ashton. Today the remainder of the branch, from Idaho Falls to Ashton, is operated by the Eastern Idaho, a Wabtec company with the reporting mark WAMX. The line is fairly well known for its fleet of GP30s and safety cab Canadian GP40-2LWs, most of which are stationed on the western portion of the railroad. The northern portion, which operates the Yellowstone branch, uses mostly GP35s.

The Eastern Idaho Railroad operates the Yellowstone Branch using these smartly-painted black and yellow geeps.

If perchance you find your way to the old Yellowstone branch on the way to the park, the bad news is that trains are few and far between. In the four years that I worked in the Yellowstone area, I only saw one train on the branch, running North to Ashton in the late afternoon. Over the week that I was there in 2017 I saw two trains, one coming off the branch into the yard at Idaho Falls on a Friday afternoon and one leaving Idaho Falls on a Wednesday morning. In speaking to locals in some of the towns along the way they all agreed that trains run simply as needed, with no guarantee of when or how far they will run when they do. In addition the Yellowstone Branch has two smaller branches that break off, one at Orvin on the north end of Idaho Falls going to Newdale, and the other at Ucon going towards Menan. Neither of this smaller branches parallel a road for any good measure of distance apart from where they pass through towns so photographing a train on these lines is even more difficult.

The good news is that the main branch runs almost due north, so sunlight is good almost all day, depending on whether you take Highway 20 (afternoon) or the old Yellowstone Highway (morning). The downside to the Yellowstone Highway is that it is no longer an uninterrupted road but rather appears and disappears at random every few miles, so chasing a train will require hopping back and forth between it and Highway 20 where on ramps are available. Traffic on the Yellowstone Branch consists of three main commodities: grain, potatoes and fuel oils. Tank cars, hoppers and those white Union Pacific ARMN refrigerator cars are the staple rolling stock seen. Since agricultural traffic is largely seasonal, traffic levels fluctuate through the year as harvests wax and wane.

Potato packing plants are equally as common as grain elevators on the branch, playing well with the Idaho stereotype. Cruddy, rusty ARMN reefers are used for this service.

Your tour begins at Idaho Falls, where the Eastern Idaho Railroad interchanges with Union Pacific. A few daily UP locals from Pocatello terminate there and EIRR switching traffic is fairly constant throughout the day. The best time to see the yard is in the morning from the northern end, where a parking lot and street parallel it on a bluff giving a slightly elevated view. In the afternoons you can see the other side of the yard in sun from Centre Avenue (the Union Pacific end) and Emerson Avenue (the EIRR end).

The Idaho Falls yard sees a lot of traffic as EIRR and UP trains switch local industries as well as prepare trains to head out on the Yellowstone Branch. Here the Yellowstone turn pulls out of the yard while another GP35 switches in the background and an SD24 rests near the yard office.

Between Idaho Falls and Rexburg the branch is pretty straightforward, literally. A clean straight shot north with a siding here and there for potato packers. After Rexburg the tracks get a bit more interesting, curving a bit with more sidings branching off at right angles for sawmills and fuel dealerships. However, they run at an angle through the city so there is no one road that parallels them. Following the tracks involves a zig-zag going from one block to another until the track reaches the other end. Just make sure to stop at every track because Rexburg is the only city I have been to where every single grade crossing is protected with a mandatory stop sign - it is easy to forget this when most non-gated crossings are protected only with crossbucks.

This cluster of elevators in Rexburg looks like it may be built around the old freight depot. The building closest to the tracks looks very much like an OSL standard depot.

At St. Anthony the elevator districts start cropping up and at Ashton the tiny town is filled and surrounded with a maze of spurs, sidings and a wye servicing Elevator Row right on Main Street. Ashton is in my opinion the most interesting of the towns, being the current end-of-track and former junction with the Teton Valley Branch that ran to Victor Idaho.

Garry, Idaho is a typical example of the scenery seen along much of the Yellowstone Branch between Idaho Falls and Rexburg. A potato packer is served by a spur at this location.

The spurs at Thornton were being reballasted during my trip.

The spurs at Thornton were being reballasted during my trip.

Ashton's elevators have their own trackmobile to switch cars when an EIRR locomotive isn't around.

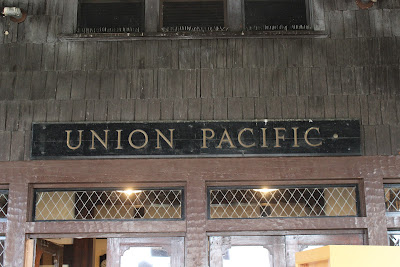

Regardless of whether or not you decide to search out the abandoned grades, the best part of ghost railfanning this line is at the terminus at West Yellowstone. There, the Union Pacific depot, baggage building and Union Pacific Lodge still stand, donated to the City of West Yellowstone. The depot itself is an excellent museum (entry fee $6.00) with a short bit of track relaid along the platform and a car from the Montana Centennial Train representing the once busy passenger traffic on the branch bringing tourists to the park.

Just to the east of the depot are the baggage building, now used by the West Yellowstone Police Department, and the Union Pacific Lodge. Interestingly, the linens from this huge hotel were shipped by train to Ogden Utah where the world's only railroad-owned industrial laundry facility existed. The building still stands and is part of the Utah State Railroad Museum complex although it is closed to the public due to its poor structural condition.

This little stretch of track is a definite bonus to a vacation to the park, so next time you head to the Yellowstone/Teton area be sure to look for it. Maybe you'll be lucky and get some great shots.

Links

Eastern Idaho Railroad website

Eastern Idaho Railroad on Railpictures.net (check out Russell Watson's pictures of the Yellowstone Branch)